The Philosopher Rabbi and the Pope: The Hasidic Banshak Who Changed Christianity After Two Thousand Years

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Rabbi, philosopher and pope - sometimes it sounds like the beginning of a joke. But sometimes, it's a serious moment when history changes its face | After two thousand years of crusades saturated with the blood of Israel, Abraham Joshua Heschel appeared - a Jew, a cosmopolitan philosopher, who decided to give Christianity its due and put an end to it | "He Who Chose Us" (Kikar Magazine)

Silence is slime.

For many years, Pope Pius XII 's name was embroiled in one of the most charged moral debates in modern history. While Europe burned in the flames of the Holocaust , the See in Rome maintained a deafening silence. His critics claimed that he had "sold his soul" by refraining from a firm public condemnation of Nazism and the extermination of the Jews, even as information flowed into his office without fail.

As early as 1942, Pius XII received chilling reports. The priest Pietro Scavizzi wrote to him that "the murder of the Jews of Ukraine is complete" and that "there is talk of two million victims." Documents recently revealed in the Vatican's secret archives prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that the Pope knew about the deportations to death camps, the gas chambers, and the extent of the massacre.

However, the response was selective and limited. The Vatican focused mainly on rescuing Jews who had been baptized into Christianity , mixed couples, or children from Catholic families. Even when the raid on the Rome ghetto took place on 16 October 1943, "under the Pope's windows", his intervention resulted in the release of only 252 converts, while over a thousand other Jews were sent to their deaths in Birkenau. Pius XII believed that neutrality was the best way to protect the interests of the Church, even if it came at the cost of his own moral authority.

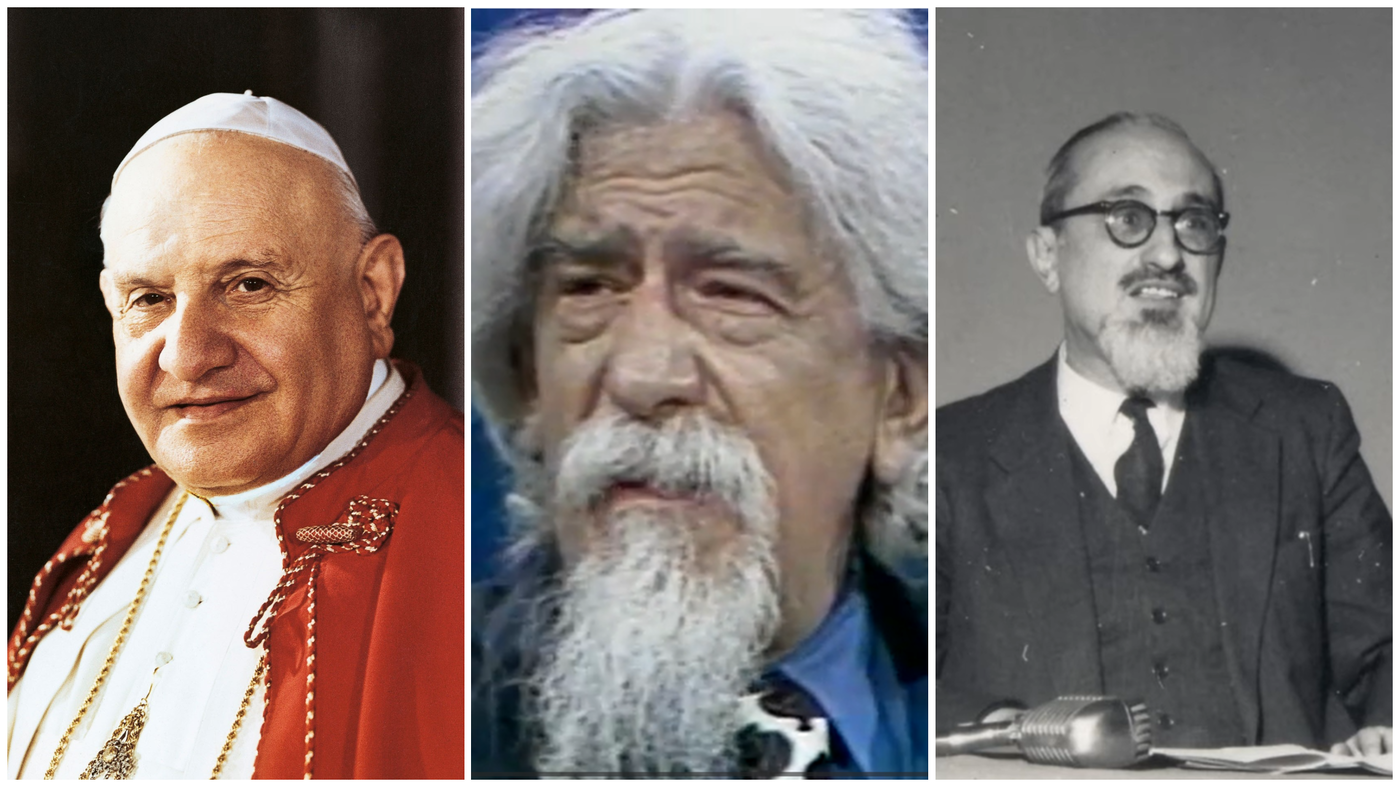

The "temporary" pope who surprises the world

With the death of Pius XII in 1958, the Catholic world was searching for a new leader. The election of Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, who became Pope John XXIII, was initially seen as the appointment of a “transitional pope” – a 77-year-old man destined to fill the role briefly and quietly.

But Roncalli had a very different past. Unlike his distant, diplomatic predecessor, Roncalli was a “people’s pope.” During the war, he was the papal legate in Turkey and Greece; he did not remain silent. He forged baptismal certificates for Jews in Hungary, pressured the Slovak authorities to stop deportations, and saved thousands of Jewish children from extermination. When he was appointed to the highest office, he brought with him that simple human compassion.

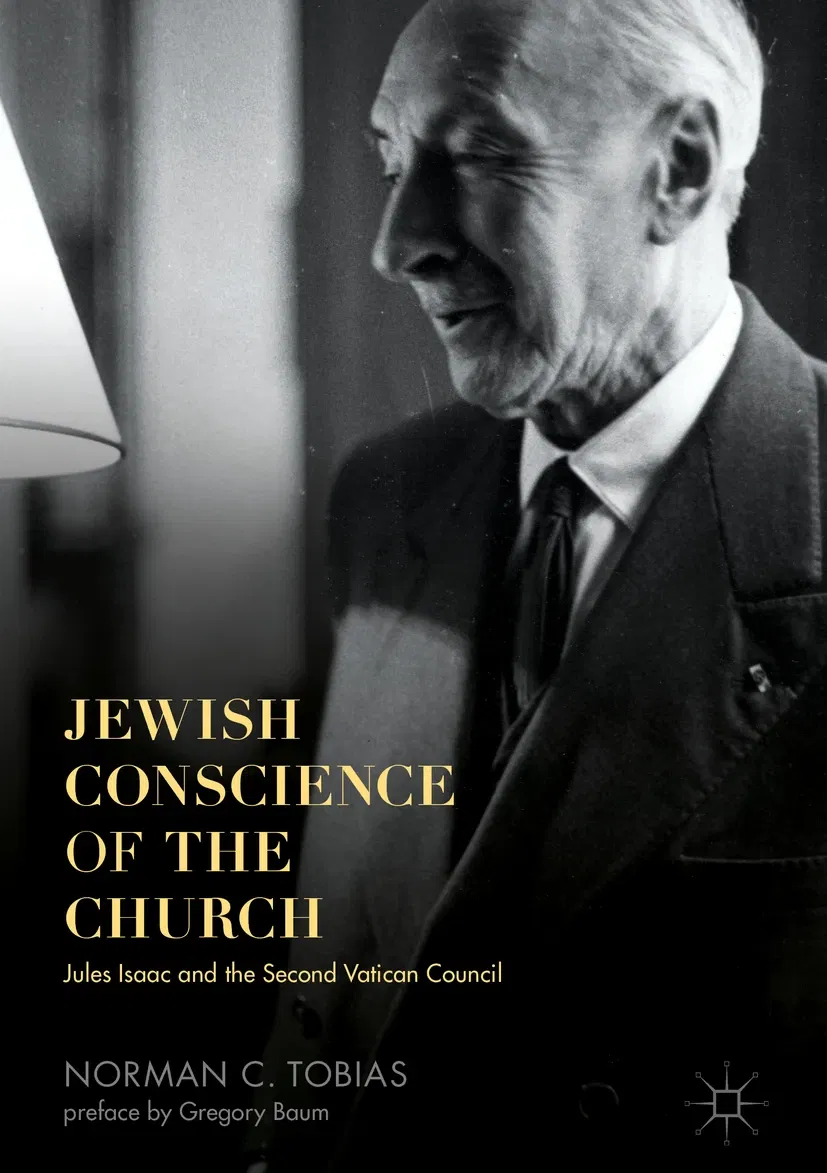

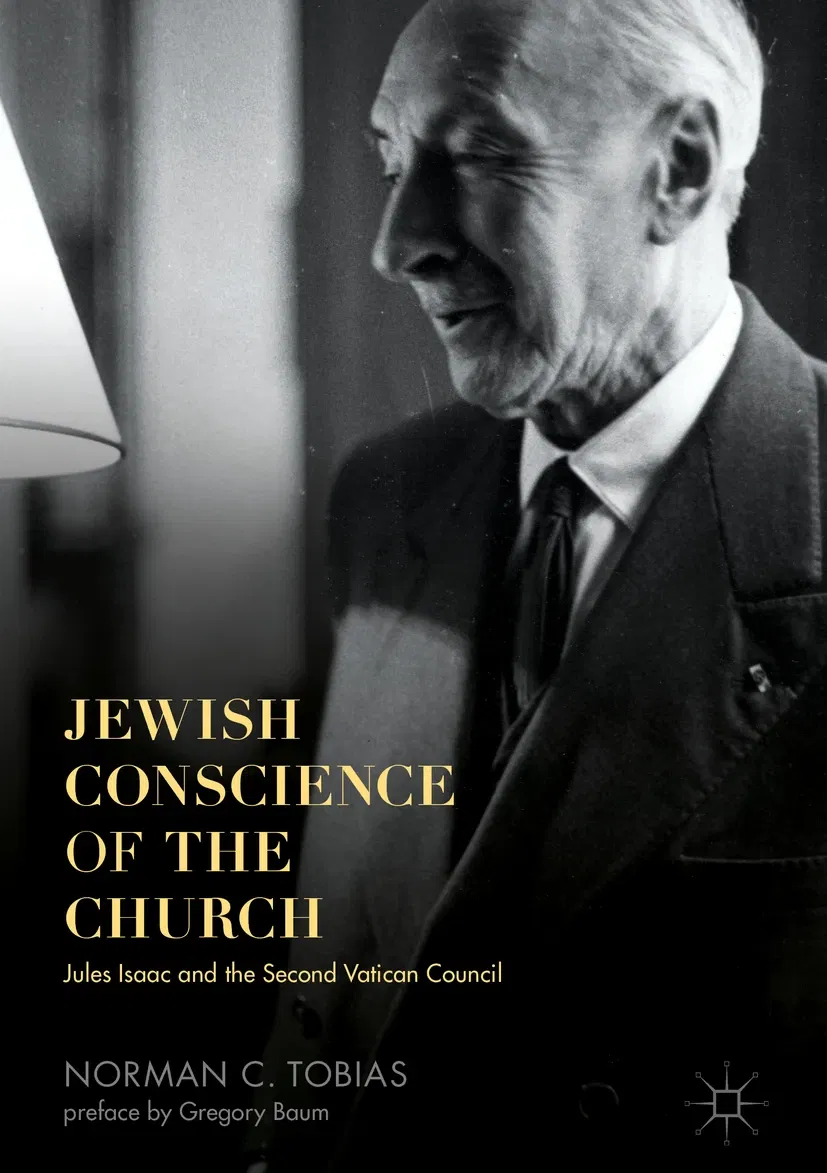

The defining moment that opened the way for change occurred in June 1960. Jules Isaac , a world-renowned French-Jewish historian who lost his wife and daughter in Auschwitz, arrived at the Vatican. He presented the Pope with a dossier detailing the roots of Christian anti-Semitism, which he called the "teaching of contempt." He argued that the Christian tradition that presented the Jews as a cursed people (APL) and murderers of that man was the foundation on which indifference to the Holocaust grew.

The Pope, moved by the words, asked Isaac at the end of the meeting: "Can I leave with hope?" John the Twenty-Third answered him with words that would become legendary: "You are entitled to much more than hope! "

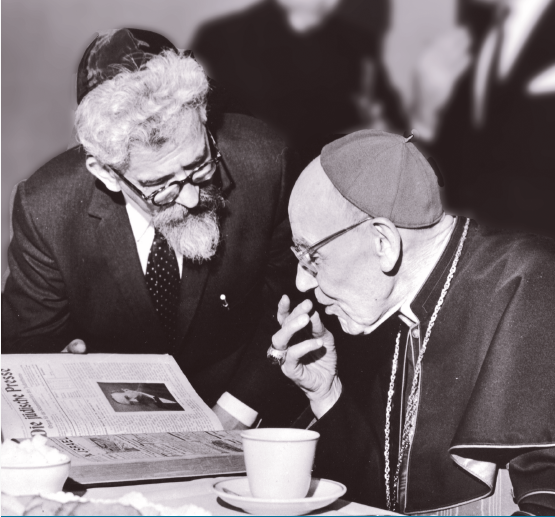

Two giants and one bridge

While Pope John XXIII opened the windows of the Vatican, across the ocean in the United States, stood two Jewish spiritual giants who would shape the Jewish people's response to the Catholic revolution. Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik , a giant of thought, and Abraham Joshua Heschel , the philosopher of primeval splendor.

Both were born into the same fertile soil of Eastern Europe, both carried illustrious rabbinical lineages on their shoulders, and both came to Berlin to earn a doctorate in philosophy – but their spiritual paths were as different as East from West.

Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik was born in 1903 in Poland, a descendant of the illustrious Brisk rabbinical dynasty . As a child, he did not attend a formal school, but was educated at his father's knees in a thorough and rigorous study of Talmud. Already in his youth, he mastered all the secrets of the Talmud before turning to secular studies. When he went to Berlin to study philosophy, he did not abandon his old world; he used the tools of Kant and Hegel to build the spiritual fortress of the "man of halakhah."

For Rabbi Soloveitchik, the Jew approaches the world with his hands holding the Torah given at Sinai. Halacha is his map of reality, the system that gives order and meaning to existence. He was a man of discipline, of personal responsibility, and of razor-sharp thought. For him, religion was first and foremost a commitment to the law of God. An inner fortress that no one can breach.

At the same time, in Warsaw in 1907, Abraham Yehoshua Heschel was born. He was a "Chassidic prince", a descendant of "Haohev Yisrael" from Apta. Heschel grew up in a world of emotion, mysticism and devotion. He said that his cradle was in the spirit of Chassidicism, surrounded by people who were sure that there was something transcendent in everything.

The meeting with Hitler

One fateful night at the Berlin Opera in the early 1930s, the young Heschel experienced the intensity of political terror that permeated even the highest halls of culture. In the middle of the performance, Adolf Hitler entered the hall, and Heschel trembled with horror as he saw the entire audience rise to their feet as one to pay homage to the terrifying figure. He could not bear the shocking sight of the masses cheering tyranny and fled the scene as quickly as possible.

He did not know then that these events marked the beginning of the personal tragedy that would strike his family: his mother, Reisel, and three of his sisters, Esther, Gitel, and Deborah Miriam, were left behind in Europe and would all be murdered during the Holocaust.

"God seeks man"

A few months later, on October 28, 1938, Heschel's life in Germany fell apart for good when the Gestapo raided Jewish homes to deport thousands of Polish Jews. In the moments when he was forced to pack his life into a small suitcase, Heschel made a choice that reflected his deep inner world: he filled two suitcases with valuable, unpublished books and manuscripts, choosing them over his clothes or any other personal possessions.

With this baggage, in which the writings were more important to him than the clothes he wore, he was taken to the Zbowenszyn concentration camp on the Polish border. Heschel managed to escape from the camp and return to Warsaw, where he stayed briefly with his family before managing to emigrate to London and from there to the United States in 1940.

Heschel arrived in New York as a penniless refugee, but with the spiritual baggage of the suitcases he had saved and the open wound of the loss of his family. He would later say that "since Auschwitz, I have only one rule of thumb for everything I say: Will it be acceptable to those people who were burned there?"

Abraham Joshua Heschel placed at the center of his thought the revolutionary insight that God is not an abstract concept or a halakhic object, but rather seeks man and demands from him a deep partnership and covenant.

He operated within a constant existential tension between Hasidic compassion and joy (the Baal Shemesh) and the demand for piercing truth (Kotzek), a tension that compelled him to bring Jewish insights to the heart of modern reality.

For him, working for social justice and "Tikkun Olam" was a form of worship, even when he was campaigning for the rights of blacks in the United States. In his approach to the world, he believed that human brotherhood stems from recognizing G-d as a common "Father." In his opinion, such a view gives every person infinite value and obliges us to Tikkun Olam out of a deep religious responsibility, or in his own formula: "G-d seeks man."

The Great Controversy and Revolution in Rome

After the Holocaust, the Catholic Church could no longer ignore the “Jewish question.” Institutional anti-Semitism and the ancient accusation of the murder of the same man had to be reexamined. The Vatican, under Pope John XXIII, sought to draft a document that would change the Church’s attitude toward Judaism —later the document “Nostra Attata.”

But to write such a document, the Church needed Jews to talk to. Here arose the great dilemma that divided these two giants. Heschel believed that dialogue with the Church was a moral and theological necessity that could not be avoided. He saw it as an opportunity to uproot the roots of Christian hatred from the world. On the other hand, Rabbi Soloveitchik was deeply suspicious of the Church. He feared that attempts at dialogue were a cover for missionary work and attempts at conversion.

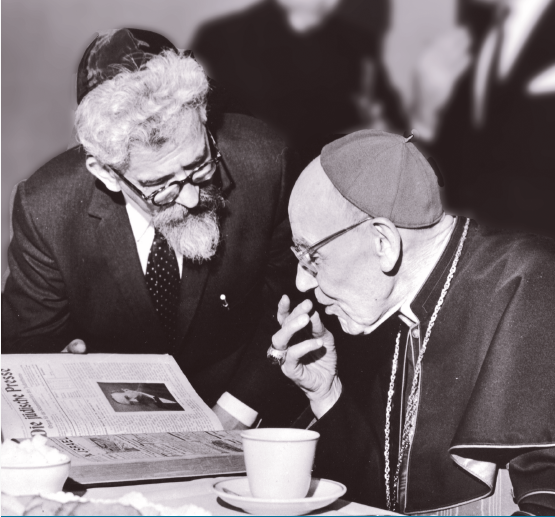

The invitation for historical change did not come in a vacuum. It was Cardinal Augustin Bae , a German biblical scholar appointed by John XXIII to head the Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity, who began the exploration. Bae turned to Jewish organizations, led by the American Jewish Committee (AJC) , for recommendations and constructive criticism on the drafting of a document that would reorganize the church’s relations with the Jews. Here began the great drama between the two spiritual giants, each of whom was asked by the AJC to advise on formulating the Jewish position.

'A people alone' or 'a light to the nations'?

In February 1964, Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik gave a speech in Yiddish to the Rabbinical Federation of America that became a seminal "Confrontation" article in the journal Tradition. Rabbi Soloveitchik argued that faith communities are unique and incomparable; each religion has its own "intimacy" and religious experiences that cannot be translated into another.

He warned that any attempt at theological dialogue would inevitably lead to an effort by the church to “reconcile” differences and eliminate the uniqueness of Judaism. For him, Jews should cooperate with Christians on secular issues such as combating anti-Semitism or social justice, but stop at the entrance to the religious fortress. He feared that dialogue was a cover for missionaryism, and that Jews were being pushed to welcome any shred of Christian tolerance simply because the church had stopped teaching the “doctrine of disgrace.” The rabbi emphasized that we must “communicate our otherness” and not try to obscure it in order to please the church.

On the other hand, Abraham Joshua Heschel saw the meeting as a profound religious opportunity. He believed that dialogue was necessary because "no religion is an island" and that Jews had a moral responsibility to influence the world of Christendom. Heschel, who was the AJC's chief advisor, drafted for them the third official memorandum submitted to the Vatican: "On the Improvement of Jewish-Catholic Relations."

In this memorandum, Heschel did not just look to the past but offered a path to the future. He demanded that the church recognize Jews as Jews, cease attempts at conversion, and recognize that religious diversity may be God's will. Heschel believed that in the post-Holocaust era, silence in the face of persecution was a sin, and that religious leaders should be "partners" in repairing the world.

Ladies and gentlemen, a transformation

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) was one of the most significant religious events of the 20th century. It was convened in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome under the motto "Aggiornamento" (update and renewal), and was attended by some 2,900 bishops from all over the world. The conference also hosted observers from the Protestant and Orthodox churches, as well as the Russian Church.

It all began in a spirit of hope under the leadership of Pope John XXIII. But in the midst of the process, in June 1963, tragedy struck: John XXIII died. There was deep anxiety in the Jewish world; many felt that the entire enterprise had gone down the drain and that his successor, Paul VI, would be too conservative and cautious. Paul did announce the continuation of the conference, but he found himself under tremendous pressure.

The struggle was not only theological, but political and international. Arab countries, led by Nasser's Egypt, exerted heavy pressure on the Vatican. They feared that any religious gesture towards the Jews would be interpreted as political recognition of the young State of Israel. In the Vatican itself, conservative elements tried to soften the text, and at one point it seemed that the conference was about to back down from its original promises.

The drama reached its peak when a draft was published that implied that the church still hoped for a "future union" of Jews with Christianity - that is, conversion. Heschel responded with a fury that shook the swordsmen. In a scathing interview with the newspaper "Maariv" and in the headlines of the "New York Times", Heschel sharply criticized the church's silence on the Holocaust and finally, without fear, he declared with a thick hint: "I am ready to go to Auschwitz at any time if I am faced with the choice: conversion or death!"

Time to change

His comments, which sounded to Vatican officials as if he were comparing them to Nazis, caused a stir in the Vatican corridors. Cardinal Bae wrote to Heschel that the interview had caused him " the greatest embarrassment he had ever experienced," after he had to endure 45 minutes of reprimands from his conservative colleagues who claimed that Heschel was "destroying the most precious plans."

In an attempt to salvage the situation, Eshel was scheduled to meet with Pope Paul VI in person on September 14, 1964. By a chilling coincidence, the meeting was held on the eve of Yom Kippur. On the morning of the meeting, while staying at a hotel in Rome under a heavy veil of secrecy, Eshel wrote a personal letter to his wife Silvia and daughter Susie: "The Pope's office expressed regret that they forgot that I could not come on Shabbat... Remove worry from your hearts, just be happy and pray."

Heschel entered the room carrying a sharp and demanding theological memorandum. Paul VI was friendly but firm, making it clear that he could not change doctrine at the request of “external factors,” but promised to consider his words. Heschel left the meeting worried, but his words were already beginning to seep through.

In the end, Heschel's persistence and the alliance he made with Cardinal Bea bore fruit. On October 28, 1965, by an overwhelming majority, the declaration "Nostra Attata" (= In Our Time) was approved. For the first time in two thousand years, the Catholic Church cleared the Jewish people of the charge of "murder of the Father of the Church", condemned anti-Semitism and recognized Judaism as a living religion with eternal value.

Heschel succeeded where many failed: he forced the Christian world to look in the mirror of Auschwitz and mend its ways.

Alongside Heschel's consolidating and founding actions, the important ideas of conservative American Jewry remained almost isolated.

Dror Bondi, a doctor of Jewish thought who specializes in the thought of Abraham Yehoshua Heschel, notes that despite his fame, Heschel remained a religiously solitary man; on Sabbath mornings he prayed in a Conservative Beit Midrash, at noon in the "shtibel" of Gur Hasidim, and on Sabbath nights he prayed alone in his home - alone will he dwell?!

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment