How Rav Hutner Overcame His Pain

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

How Rav Hutner Overcame His Pain

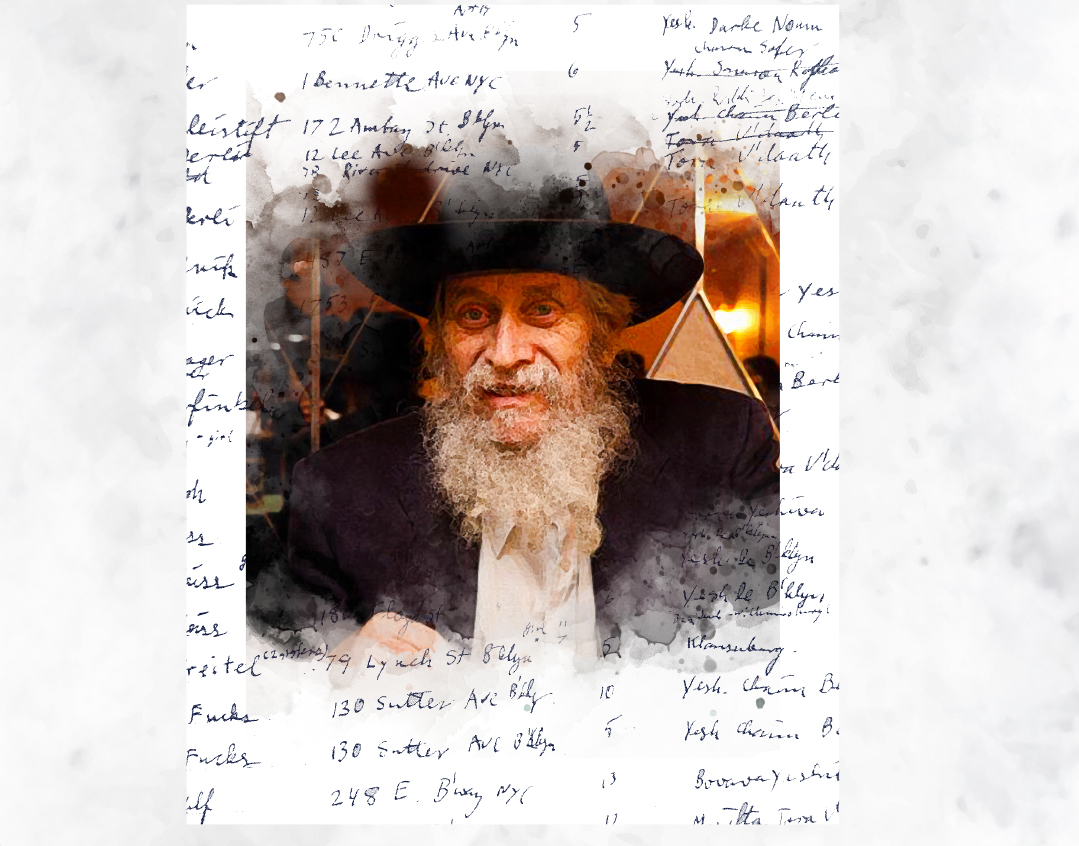

Motzoei Shabbos Story: A sincere comment by a Lubavitcher Chossid has convinced Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner, Rosh Yeshivas Rabbi Chaim Berlin in Brooklyn, to attend a charity event despite suffering excruciating pain.

By Dovid Zaklikowski for COLlive and Hasidic Archives

It was a day that Rabbi Avremel Kleinkaufman will never forget. After World War II, he was living with his mother, a young widow, in a displaced persons (DP) camp in Europe. Having lost touch with her parents and siblings, his mother assumed that she was alone in the world with her son.

Then, one day, she came home and exclaimed, “Avrohom lebt! Uncle is alive!” She had seen a note posted in the town square asking for information on the Karp family from Frampol. The note was signed by Avrohom Karp, her brother.

In the years that followed, Rabbi Karp became like a father to young Avremel. When Rabbi Karp and his sister immigrated to North America, Avremel spent his summers with his uncle in Montreal. Rabbi Karp, a teacher, purchased Avremel his first pair of tefillin.

As a teenager, Avremel enrolled in Yeshiva Rabbi Chaim Berlin in New York. When Rabbi Karp came to New York, he would discuss Avremel’s progress with the dean of the yeshiva, Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner.

“He was like a father to me in every sense,” recalled Rabbi Kleinkaufman, a lecturer at Yeshiva of Far Rockaway and translator of several Jewish classics. “He made it his business to go ask about how I was doing.”

One winter, Rabbi Hutner broke his foot and was not able to deliver his regular classes in the yeshiva. During this time, Rabbi Karp made one of his visits to New York. The next week, Rabbi Hutner returned to school and called Avremel into his office.

When Avremel entered, the dean told him, “I want to tell you what your uncle coerced me into…”

Rabbi Hutner told Avremel that every time Rabbi Karp visited, he gave a donation to the Yeshiva. “Last Tuesday, he did the same, but this time it was a substantial amount.”

Rabbi Hutner asked Rabbi Karp how he could afford such a large amount.

“A Jew needs to make the effort,” Rabbi Karp replied simply.

Shortly after this conversation, Rabbi Hutner said, he had been invited to a charity event that he normally would have attended. Because of his broken foot, however, he had declined the invitation.

That was when Rabbi Karp’s words began echoing in his ears: “A Jew needs to make the effort.”

The morning of the event came, Rabbi Hutner said, and he knew that he had to go, “If I didn’t go, I wouldn’t have any rest.”

He had suffered through the event in excruciating pain, yet he continued repeating Rabbi Karp’s words to himself: “A Jew needs to make the effort, a Jew needs to make the effort, a Jew needs to make the effort.”

“This is what your uncle did to me,” the dean said to Avremel. “Now go back to learn.”

In the Right Direction

He sent hundreds of refugees to yeshivah and created a generation of Torah scholars but no one even knew his name. Who was Shlomo Friedmann?

Photos: Family archives

The refugees who staggered off the ships in New York after finally leaving blood-drenched Europe had made it through the war with their bodies intact, but their spiritual lives were in danger.

Shlomo Friedmann was an immigrant himself, with no financial or organizational backing, but dozens of men owe their yeshivah education to a man who cared enough to show up when they were at the crossroads

Rabbi Avraham Kleinkaufman of Far Rockaway, a maggid shiur in Mesivta Rabbi Chaim Berlin and in Yeshiva of Far Rockaway, was just nine years old when he encountered the man who changed the trajectory of his entire life.

Orphaned of his father, he and his mother, Shaindel Kleinkaufman, stepped off the General Langfitt onto Pier 54 in New York. After fleeing with her young child to Uzbekistan during the war and years in a DP camp, Mrs. Kleinkaufman was hoping to finally find stability for herself and her son in the goldeneh medineh.

As they joined the crowd of disembarking passengers, a 24-year-old young man in a light brown suit and hat noticed young Avremel’s peyos and strode up to them.

“Excuse me,” he approached them, clipboard in hand. “Vos tracht ihr tzu tun mit ayer zohn [What are you planning to do with your son]?” he asked in a pronounced German accent.

“I’m sending him to public school,” Shaindel replied. “I will hire a rebbi to learn with him a bit in the afternoon.”

“I have an idea for you,” the young man countered. “The Bobover Ruv just opened a cheder on West 86th Street on the Upper West Side. Until you get settled and find a job and apartment, why don’t you send him there? The Bobover Ruv will take care of him.”

And that is how young Avremel Kleinkaufman, along with dozens of other young refugees, was placed in yeshivos in the chaotic aftermath of the Holocaust.

At the Docks

W

hen Rabbi Kleinkaufman told me about his benefactor, who appeared as if from nowhere and set the tone for his whole future with just a few well-timed words to his mother, my curiosity was piqued. My interest intensified when I learned that Shlomo Friedmann, the young man at the pier, who wasn’t married, not formally affiliated with any organization, and an immigrant himself, was responsible for placing dozens and dozens of children in yeshivos in the aftermath of the war. He would regularly go to the docks to greet the new, bewildered passengers and gently urge parents to send their children to yeshivos.

Intrigued, I set off on a mission to retrace the footsteps of this virtually unknown hero, but was stymied at first. Somehow, despite his prolific endeavors in kiruv and chesed, he had managed to slip under the radar. But eventually, my research yielded fruit, and I was entranced to see the layers of this seemingly simple man peeling back to reveal the tzaddik within.

Born in 1926 in Breslau, Germany (currently Wrocław, Poland), Shlomo was the youngest of three siblings. His father Yehuda Friedmann fought in World War I and ran a business importing animal feed for horses. By the mid-1930s, though, the Nazi takeover of Germany had begun to cast a shadow over Shlomo’s childhood. He never told his children much about that time in his life, except that because the Hitler Youth was constantly marching through the streets, “he used to stay home and drive his mother crazy,” says Mr. Friedmann’s son Yossi, who I met through Rabbi Kleinkaufman. By 1939, they knew it was time to leave. Miraculously — due to some connections from his army days — Mr. Friedmann was able to get his family and even his furniture (including their seforim shrank) out of Germany.

Arriving in America in March 1939, Mr. Friedmann Sr. soon secured a job with a Jewish immigrant aid association. It didn’t last long, however.

“They wanted him to work on the second day of Pesach, because they were Reform Jews — they didn’t hold of the second day of Yom Tov,” Yossi Friedmann recounts. But Mr. Friedmann refused to budge. Standing his ground, he gave up the security of a steady salary and opened his own business, fixing typewriters.

Settling in the Upper West Side, the Friedmanns sent young Shlomo, now just bar mitzvah, to public school. He later attended an agricultural high school in Queens. It wasn’t until after the war, when the Bobover Rebbe immigrated to the states, that Shlomo began learning night seder in the Bobover shtibel on the Upper West Side.

Shlomo ran a weekly Pirchei program in the local shul, where the Rebbe spent his first Shabbos in America. It was Shlomo’s first time meeting a chassidic rebbe and it would prove to be a pivotal encounter. Mr. Friedmann would go on to send many boys, including Rabbi Kleinkaufman, to the Bobover Rebbe’s yeshivah.

Ironically, while Shlomo himself never had a typical yeshivah education, he developed a burning passion to send children to yeshivah. “It could be because of his own experience,” Yossi Friedmann speculates. Perhaps the fact that he never had the privilege of a Torah education gave him the drive to ensure that other young boys would.

When the war was over, and Shlomo was just in his early twenties, he began going to the docks regularly looking for children and directing them to yeshivos. “There are dozens of kids who learned in yeshivah because of him, including me,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman shares. Mr. Friedmann, he says, “might have done more for chinuch in America than all the rich people or huge organizations.”

Veiled by Obscurity

R

abbi Kleinkaufman’s story intrigues me, and I start trying to find out more about his benefactor, who passed away in 2019. My first step is a treasure trove of papers that Rabbi Kleinkaufman shares with me, which he received from Mr. Friedmann’s children. Looking through the correspondence, I’m struck by the scope and depth of his caring for Jewish children. Working as an individual, with no high-profile contacts, he reached out to anyone likely to help, no matter how remote the chance, to place just one extra child in yeshivah.

One example is a letter from 1951 addressed to Manfred Fulda at 220 Wadsworth Ave in Washington Heights, NY:

Dear Chaver,

Isamar Lipshitz, a chaver of Zeirei Agudath Israel of Midtown, told me that you are the president of the Yeshiva Student Council of Yitzchok Elchanan. I understand that one of your activities is to influence parents to send their children to yeshivos.

[L]ast year I went to the HIAS, to make friends with the children recently arrived from Europe, and told them to go to their neighborhood yeshivah, giving them the nearest one upon moving into apartments. Many of the parents agreed with me, but have not responded immediately. Enclosed is a list of some of these boys, which have to be visited during the vacation. Have your members go to these people, and see to it that they register in suggested yeshivos…

Wishing you lots of success,

Salomon Friedmann

Not only did Mr. Friedmann work to place boys in yeshivos, but recognizing the importance of summer camp, he did everything in his power to make sure the children on his lists were set up in religious camps as well. When money was an issue for parents, he fundraised to make it happen, even opening his own “Salomon Friedmann Camp Fund” at Camp Bais Yaakov. I discovered this in another letter, this one from 1957, addressed to Mr. Ullmann at Camp Bais Yaakov.

In reference to camper… I return to you signed registration blank and $50 in 5 checks. The balance of $39.55 will be submitted soon to you… I am thanking you for your fine cooperation.

Of the five checks, the first, for $25, is from the Salomon Friedmann Camp Fund. The other four are from private individuals and small businesses.

And Mr. Friedmann’s care for campers wasn’t just limited to paying their fees. He spent summers in Camp Agudah, in its early days in Highmount, where he frequently placed children. Recognizing that the gap in their education could prevent boys from succeeding in yeshivah, he would tutor them in kriah.

But, as I soon find out, despite his far-reaching activities, his name has somehow receded into obscurity. His name never appeared on any organizational letterheads, nor was he honored at any dinners. A search through the Agudah archives turned up no information. When I reached out to a prominent activist whose work overlapped with Friedmann’s, he said the name “didn’t ring any bells.”

Rabbi Moshe Kolodny, Agudath Israel’s archivist emeritus, tells me Mr. Friedmann’s lack of name recognition isn’t as shocking as it might seem. “He basically worked independently,” Rabbi Kolodny says. Operating without any organizational framework or fanfare, Mr. Friedmann did whatever needed to get done, be it tutoring struggling students gratis, getting young orphans into camp, or directing immigrants into yeshivos and Bais Yaakovs.

Rabbi Kleinkaufman tells me about the visit he paid to Friedmann in his later years, hoping he could track down some of the other children he placed in yeshivah, so they could give him the recognition he deserved. To his surprise, he found boxes full of lists. He shows me lists of dozens of boys’ names, some handwritten, some typewritten — all placed in yeshivah by Shlomo Friedmann. The lists record each boy’s (and that of some girls) address, yeshivah placement, and pertinent background information.

I was delighted to see the lists, sure they would help me in my efforts to learn more about Shlomo Friedmann, but my goal proved to be maddeningly elusive. I spent many long months searching for these boys, mostly without success.

When I reached out to one yeshivah for permission to check their alumni records, they responded as follows: “Unfortunately, due to the many moves from different neighborhoods that the yeshivah was made to endure over the years, we have a very limited amount of this type of historical record. Regrettably, it seems that we don’t have the information you are looking for at this time.”

Undeterred, I put name after name into Google. I got no results for Leibish Teitelreis, (“Did you mean: Leibish Teitelbaum?” Google asked helpfully), and a search for the Spodic brothers, Moses, David, and Leibel, from 1359 E. New York Ave, led to a deceased Dr. David Spodick born in 1927 in Hartford, CT. He would have been in his mid-twenties in the early 1950s, not 13 as the list indicates, and definitely not a young immigrant yeshivah boy from Mr. Friedmann’s list.

A Google search for “Moshe Garfinkel Brooklyn NY,” turned up someone born in 1975 — too young to have been a Shlomo Friedmann beneficiary. I smiled when a broadened search for just “Moshe Garfinkel” turned up the antagonist of Mishpacha’s recent Family First fiction serial, Lie of the Land, himself the subject of a search that takes up most of the story.

I was close to admitting defeat when I dialed Michael Tepler, age 85, from Brooklyn. “I have a list with the name Michael Tepler from 1497 St. Marks Avenue in Brooklyn who attended Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin at age eleven and a half,” I venture, after briefly telling the man who answered the phone about my quest for memories of Shlomo Friedmann. Luckily, Mr. Tepler did not hang up on me. “That’s me!” he exclaimed.

Mr. Tepler, from Tomaszów Lubelski, Poland, was born in July 1939 — less than two months before the war broke out. Fleeing southeastward to Rava-Rus’ka, the Teplers were banished to Siberia as a punishment for not accepting Russian citizenship, but survived. At the war’s end, they made their way to a DP camp, where they stayed until 1950. Then, when Michael was already 11 years old, they boarded a ship for the US.

Mr. Tepler thinks back to see if he remembers Shlomo Friedmann. “I don’t remember the name, but I do remember somebody meeting me at the docks… He spoke to my parents about sending me to yeshivah,” Mr. Tepler recalls. “He was mekarev people.”

While Friedmann’s name fell by the wayside, his impact did not. Mr. Tepler went on to attend Chaim Berlin, continuing to study in yeshivah while attending Brooklyn College at night. Today, his children and grandchildren are all shomrei Torah u’mitzvos, and his grandson Rabbi Dov Tepler is a rosh chaburah in BMG and a popular lecturer on TorahAnytime.

Critical Juncture

W

hile I didn’t make much progress with the lists, Rabbi Kleinkaufman himself was a gold mine of information. Sitting with him in his study of his Far Rockaway home, nicknamed “Yanover Kloiz” after his father’s hometown, and listening to him share his background, I was sobered thinking how different his life would have looked if Shlomo Friedmann hadn’t reached out to his mother at that critical juncture.

His parents, Dovid and Shaindel Kleinkaufman, had fled Poland in 1939 when the Germans invaded, hoping they’d find safety in Ukraine. It was not to be, however. “I was born May 26, 1941,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman recounts. “I guess the Germans heard that I was born, because a month later — June 1941 — they attacked.” The situation deteriorated rapidly.

“When they came into Ukraine, my father disappeared, and my mother was left alone with an infant,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman continues. Managing to flee to safety in Uzbekistan, Shaindel spent the war years in relative safety, returning to Poland after the war in search of lost relatives. But the violence and pogroms directed against returning Jews made it clear that Poland was hardly the welcome haven that she had hoped for.

After only a month, she and five-year-old Avremel made their way to the American zone of Germany, staying in a number of DP camps — the longest stay being in Foehrenwald. It was here, under the tutelage of his beloved rebbi Rabbi Meilech Wieder, that Avremel acquired his first taste — and love — for learning. “The Klausenberger Rebbe had founded chadarim… and there I started learning Gemara. We learned in cheder from an hour before Shacharis every day till after Maariv in the summer. It was a very long day.”

Friday afternoon was the boys’ only time off, and they kept themselves busy with an unlikely occupation: watching the printing of a special DP-camp edition Shas, among other seforim. “We children were fascinated,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman remembers. “I was eight, nine years old at the time. We used to go there to watch these huge presses. Big sheets came off there, and then they were cut and bound and they printed the Shas.”

Printed with the help of the U.S. Army and known today as the “Survivors’ Talmud” or the “US Army Talmud,” the special edition Shas had a unique — and grim — title page: a wheelbarrow with bodies in it.

For the young boys, though, there was a special element of excitement in the publication of the seforim: the overruns. “We traded them like, l’havdil, baseball cards here,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman recalls. Sometimes the boys were lucky enough to collect a whole sefer, and young Avremel obtained a cherished copy of the sefer Mateh Ephraim by Rav Ephraim Zalman Margolios.

Survivors in the DP camps typically left to Eretz Yisrael or the United States. With her married sister opting to go to America, Shaindel Kleinkaufman decided to follow suit — but first, her son had to learn English. She hired a gentile German woman to teach him on Friday afternoons, his only time off from cheder.

“So this German woman used to come on a bicycle and she would teach me English, so to speak. She taught me the alphabet. I was the only child in cheder who could write from left to right,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman describes. But far more interesting to an eight-year-old boy was his teacher’s bicycle. “I said to her, ‘You know what? My mother’s not here. Why don’t you give me your bike for an hour — let me ride it, and I’ll give you a can of sardines.’ That was the currency in the DP camps. And so she readily agreed,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman says. “It was my first time playing hooky.”

Despite his frequent absences from “class,” Avremel started to practice writing his name in Latin letters on everything he owned — including his prized sefer Mateh Ephraim. Somehow, though, in the course of all the preparations for moving to the United States, the sefer disappeared, only to resurface decades later.

In the 1980s, Rabbi Kleinkaufman was serving as the learning director in Camp Bnei Torah (today known as Camp Horim). The Shiloh publishing company used to bring truckloads of sheimos to bury at the campgrounds and one day, a bochur named Shmuel Gewirtzman came running into the dining room, saying that he’d noticed a decrepit sefer in the sheimos pit with Rabbi Kleinkaufman’s name on it. Rabbi Kleinkaufman ran out, only to discover that another truckload of sheimos had already been unloaded on top of the previous one.

“Chevreh,” he said, “we’re not moving from here until we find the sefer!” They did, and now Rabbi Kleinkaufman shows me his treasured Mateh Ephraim.

“This is the source of my love for seforim,” he says.

Still, despite Avremel’s advanced Gemara knowledge and his early love for seforim, his future as a talmid chacham — perhaps even as a religious Jew — was far from certain as he reached American shores.

“My mother wanted me to be a regular citizen,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman says. “She was planning to send me to public school.”

It was the encounter with Shlomo Friedmann at the docks that changed the course of Rabbi Kleinkaufman’s life. Mr. Friedmann enrolled him in Bobov, and when the Kleinkaufmans moved to the Lower East Side, it was a natural next step for Shaindel Kleinkaufman to enroll her son in Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yaakov Yosef (RJJ). At his farher, Avremel realized something unusual was going on when the menahel Rabbi Dr. Hillel Weiss interrupted him, calling the roshei yeshivah, Rav Mendel Kravitz, Rav Shaya Shimanovitz, Rav Zeidel Epstein, and Rav Yitzchak Isaac Tendler (Rav Moshe Feinstein’s mechutan) into the room.

“I was nine years old. I knew the first perek of Kiddushin, shakla v’tarya be’al peh — that’s almost 40 blatt,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman recalls. “I started rattling off the Gemara… and I saw that they were nispael. I don’t think there was anything special. I was probably a pretty good kid, but I think most of the kids [from the DP camp cheder] were able to do that.”

In America, though, this level of mastery from a nine-year-old was a highly unusual feat.

“The trick there was, you started learning the Gemara without any havanah, just to get the rhythm,” Rabbi Kleinkaufman says, explaining the prewar European methodology. “It says ‘zemiros hayu li chukecha.’ It’s a rhythm, it’s a song, it’s a song we learned — the song of the Gemara.”

Advanced learner though he was, Avremel had clearly become more culturally American by the time he entered Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin at age fourteen.

“I took my tefillin and a little Gemara and the Yankee baseball cap I was wearing on weekdays,” says Rabbi Kleinkaufman, recalling his solo arrival for the entrance exam. (His mother had to go to work and couldn’t accompany him.)

“I walked into Chaim Berlin, which was a massive eight-story building, and as I walked into the lobby, I saw this giant of a man — who turned out to be Rav Shlomo Freifeld. He looked down at me, and he saw my peyos sticking out from under my baseball cap. And he said, ‘Di bist a Yankee chussid?’ Are you a Yankee chassid?”

Even as Rabbi Kleinkaufman continued on to more established yeshivos after his early stint in Bobov, Shlomo Friedmann continued to be an unobtrusive background presence, checking on him and ensuring he was adjusting well to each new environment. Rabbi Kleinkaufman remembers seeing him when he was 21 and newly married, learning in Kollel Gur Aryeh in Crown Heights.

“I used to sit at this long table. Rav Yonasan David was sitting at one end, and I was sitting at the other, learning with his brother, my chavrusa. Then I look up all of a sudden, and sitting across the table from me is Shlomo Friedmann. I hadn’t seen him in years.

“ ‘Reb Shlomo, what are you doing here?’ ”I said.

“ ‘Just keep learning,’ ” he replied. “ ‘I just came to shep nachas.’ ”

Redirected Passion

AS

the stream of postwar immigrants slowed to a trickle, Mr. Friedmann began to seek other avenues to express his tremendous love and concern for his fellow Jews. He taught at a number of yeshivos, including Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim of the West Side. It was there, in the mid-1960s, that he was introduced to the kindergarten teacher, Miss Devorah Flack, who soon became his wife.

They were well matched; she was also the type of person to do heroic deeds without fanfare. She had become a baalas teshuvah well before it was a popular trend. As her son Yossi says, “My mother once told me that when she first became religious my grandpa said to her, ‘I sent you to a Talmud Torah just to learn about your heritage — I didn’t expect you to become a fanatic!’ ”

After their marriage, the Friedmanns moved to Crown Heights, and Shlomo learned in Rav Yisrael Zev Gustman’s yeshivah.

In the 1970s, Mr. Friedmann taught in the Karlin-Stolin yeshivah in Brooklyn, under the leadership of Rabbi Nosson Scherman, who later became the famed general editor of ArtScroll.

“The man was a tzaddik,” Rabbi Scherman says emphatically. When I tell him about Mr. Friedmann’s work getting boys into yeshivos after the war, he isn’t surprised. “That’s the kind of person he was. He just loved Klal Yisrael. He would do anything to help another Yid.”

As I interviewed Mr. Friedmann’s colleagues and acquaintances from the postwar decades, I began to notice a remarkable pattern: a marked contrast between the memories of those who knew him incidentally and those who knew him more intimately. The former category barely remembered him, if at all. The more I heard, “his name doesn’t ring a bell” — despite his prolific activism — the more I realized how much he eschewed honor and acclaim. But for those who knew him up close, the theme of the quiet tzaddik is one that runs consistently through every interview.

“Yomam v’laylah, he was helping people,” says Rabbi Yanki Borchardt, who remembers Mr. Friedmann as his second grade rebbe in Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim of the West Side.

He was “a tremendous tzaddik,” recalls Faygie Borchardt, who taught special-needs children with him at Yeshiva R’Tzahd in the 1980s. “My husband always used to say, the people that I think institutions should honor at their dinners should be people like Shlomo Friedmann, because he was very humble, very unassuming, very dedicated and caring about what he did.”

About three decades after meeting Rabbi Kleinkaufman and so many others on the docks, Mr. Friedmann perceived once again a need for his unique brand of activism as scores of immigrants from the Soviet Union began to arrive on American shores. Many of R’Tzahd’s student body were new immigrants from the Soviet Union, and Mr. Friedmann focused his energies on facilitating their growth in Yiddishkeit.

“He had a passion for kiruv,” says his son Yossi. “Later in life, back in the 1980s when a lot of Russians were coming, he was also involved in getting people into yeshivah.”

Hidden Greatness

IN

1968, Shlomo and Devorah Friedmann moved to Flatbush, where their three children were born: Yossi, Tzipora (Fraiman), and Chana a”h. Naturally, Shlomo’s dedication to seeing children receive a Jewish education encompassed his children as well: Yossi attended Yeshiva Yagdil Torah in Boro Park and later Chaim Berlin, and Tzipora attended Bais Yaakov D’Rav Meir. And Mr. Friedmann made sure that Chana, who was deaf, would also receive a Jewish education.

Mrs. Goldie Schechter grew up with Mr. Friedmann’s children in Congregation Gvul Yaabetz in Flatbush, where her father, Rav Dovid Cohen, serves as rav. She remembers Mr. Friedmann as a “a gentle person, always smiling, and he really took care of Chana, his daughter.

“In our generation, if someone had a deaf child there was nothing to do… Where are all those people from my generation? They were hidden away… as if they didn’t exist. And he wasn’t like that. He encouraged Chana so much.”

Mrs. Schechter shares that Mr. Friedmann was instrumental in raising funds for HID, now HIDEC, the Hebrew Institute for Deaf and Exceptional Children, which Chana attended until age 15. “

I know he was very, very makpid, and proud that Chana was going to get a Jewish education,” she says.

Mrs. Schechter is shocked when I tell her that Mr. Friedmann, whom she knew as a humble, obscure congregant from her father’s shul, had sent so many boys to yeshivah.

“I’m floored,” she says. “It was a hidden piece to him that I never knew existed. And I know that this is bandied around and used and abused, but he must have been a tzaddik nistar. It scares me that I grew up seeing this man over time, thinking he’s one way… and now I’m being told, you know, he saved hundreds of boys from going to public school.”

Rabbi Kleinfkaufman chokes up a bit when he tells me about the time his past and present converged. It was decades ago that he went to visit his son, who was a camper in Camp Agudah. His son pointed out a bunkmate, and looking up, he saw to his surprise, that the boy was standing next to his father… Shlomo Friedmann! Rabbi Kleinkaufman, always acutely aware of the debt of gratitude he owed Friedmann, took the opportunity to share his history with his son.

“I would have gone to public school without him,” he told Yossi. “If there’s anyone to whom I owe everything, it’s him.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1077)

All credit goes to Dovid Zaklikowski,Tzivia Meth,COLlive, Hasidic Archives and Mishpacha

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment