"Dad never said 'Don't go to the army'": Rabbi Ovadia Yosef's religious-nationalist daughter

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

All credit goes to Dana Bezalel & https://www-makorrishon-co-il

Rivka Chikutai, the religious-national daughter of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, has chosen a different path from her brothers and sisters. In a new book, she recounts her family's version of her father's life story, revisiting the loneliness she experienced at the Ashkenazi seminary where she studied, and cherishing the hours of study with her father, "which even my brothers didn't get to have." All credit goes to Dana Bezalel and Makor Rishon

The Israeli flag flies proudly over the entrance gate to the home of Rivka and Rabbi Yaakov Chikutai in the city of Modi'in, and a chain of blue-and-white pennants hangs from the nearby railing. In the yard of the house are colorful toys and small chairs, used by their 15 grandchildren, five sons and a daughter. The sons all served in the IDF and currently work in various fields, from high-tech to management. The daughter did national service and has a master's degree in chemistry from Bar-Ilan University.

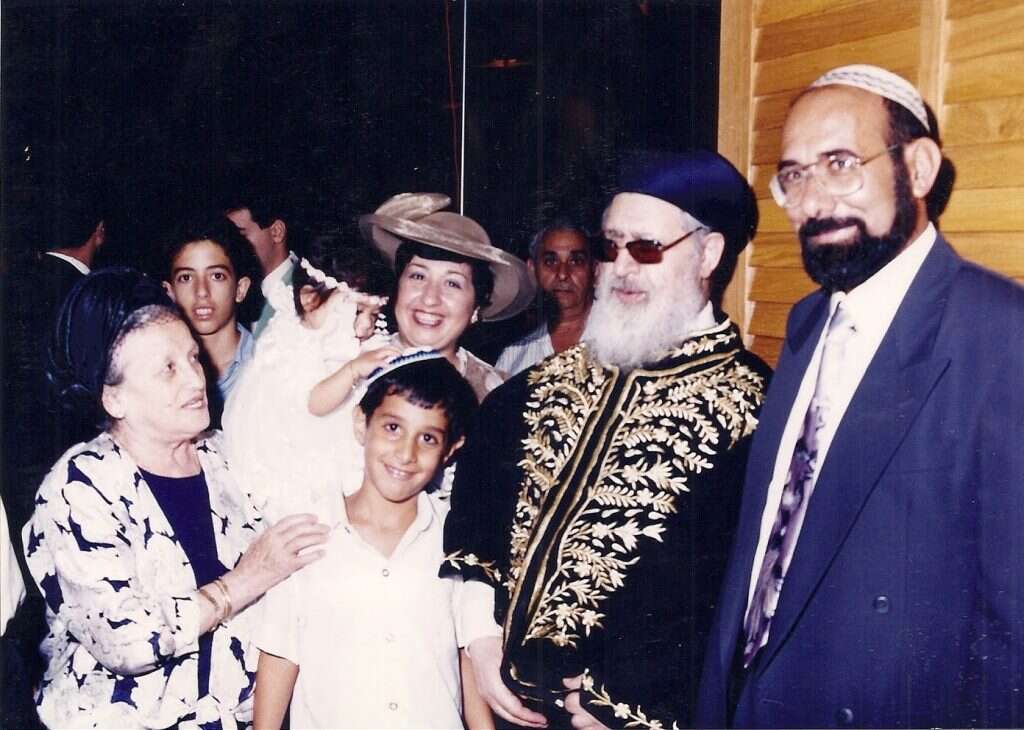

These details do not fit into the initial image we might expect of the daughter and grandchildren of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, the late spiritual leader of the Shas movement. Rivka Cikotai, the rabbi's eighth daughter, chose a slightly different path than her siblings. In anticipation of the ninth anniversary of her father's passing, which was recently noted, she published, together with her writing partner, Itamar Edelstein, the book "Beit Yosef" (published by Yedioth Sfarim), in which she recounts the life of her renowned father from a personal angle, and tells of unknown sides of the personality of the revered posek and leader. Between the pages of the book, the image of Rabbi Ovadia is revealed, the husband, father, and grandfather, who knew how to embrace his children even when they chose their own path. He describes the sharp man who sat with the world's saints and even mediated between clans and criminal organizations, but also the sensitive man who sat and cried with women in mourning who poured out their blood. A smile on his face.

The first seeds of Rivka's independent path were perhaps planted in her youth, when she studied at an Ashkenazi Haredi seminary in Tel Aviv. The question of the prayer style then sharpened the differences between her and most of her friends, and created a difficult experience that has burned into her to this day. "My father, who was then the rabbi of Tel Aviv, wanted us to continue praying in our own, Sephardic style," she says. "He wrote a letter to the school principal, requesting that the Sephardic girls pray according to the Beit Abba style. The school agreed, but outside the classroom. And so I and two other Sephardic friends prayed outside the classroom. We felt like we were being punished, because anyone who was late was punished by staying outside. This lasted until Rosh Chodesh, when the whole class prayed together, with a cantor and Hallel. That morning my friends told me: 'With all due respect to your father, we are not staying outside, we are going into the classroom.' I told my father and he was silent, I could see that he was very hurt. Then he told me: 'You are right, you should pray according to the Beit Abba style.' I suggested that I pray at home before school, and during prayer I would sit in the classroom and read the Psalms. The principal did not agree. And so every day until the end of high school, for four years, I prayed outside."

Later, when she sent her children to religious-national education, Rivka felt a kind of corrective experience: "When my children went to study at Noam School in Jerusalem, we received a list of books and it said that they had to bring a siddur 'in the style of Beit Abba.' I felt like I was closing a circle and I said thank God, blessed be He."

What does it do to a teenage girl to start the day separately from the rest of the class, for years ?

"That's the problem, that no one thought about what it was doing to my soul. Why was it so hard for me with religion? I'll tell you the truth: If it weren't for my father, I wouldn't be religious. I would have kicked everything. Is it any wonder I rebelled? I was lucky that he embraced me."

Debate about college education

The word hug recurs throughout the conversation. Rivka describes herself, with her characteristic honesty, as a rebellious child. But the more she rebelled, she says, the more she hugged. "I wanted red - wear red. I wanted a radio - listen to the radio. I got what I wanted. He didn't let me get off track, he hugged me all the time and looked after me. My sister went and told the teacher that every now and then I go to watch TV at the neighbor's. The teacher called me, I said, 'What's wrong, I didn't see it.' I came home crying. My father told my sister: 'You don't wash dirty laundry outside, come and tell me.' Then he called me and said: 'Okay, go watch TV without anyone knowing.' Everyone thought he was probably scolding me, but he wasn't. He knew that if he told me no, I would do it in secret. He never told me it was forbidden. It made me whole in my own way and not hate religion. The religion I received through school distanced me. I am a person who needs to be understood, I can't do things according to the commandments of learned people."

After her studies at the seminary, Rivka wanted to study at Jerusalem College, but she encountered opposition from her father. "He didn't want to listen to me, so I wrote him a letter about how hard it was for me at Beit Yaakov, how I left there without a shred of faith, without knowledge of halacha, we only studied Ashkenazi rulings. I wrote that I had no friends from there. I wrote to him, 'I know you, Dad, that you are a judge, when you want to rule on a case you check, but here you didn't check at all. Invite Rabbi Kupperman, the head of the college, listen to him, and then decide. It's impossible that because you don't like your friends, you will ruin my future.' That's what I wrote to him, a twenty-year-old girl. Look how impudent I was.

"I put the letter on his pillow, and I stayed awake. At two in the morning, before he went to bed, he read the letter, left the room and told me, 'Okay, tomorrow morning you'll call Rabbi Kupperman.' In the morning I got up early, looked up the number in the phone book, called Rabbi Kupperman and told him, 'Hello, this is Rabbi Ovadia Yosef's daughter speaking ('I've never introduced myself like that, why would I be patronizing you,' Rivka comments), my father wants to talk to you. I want to study at college and my father doesn't agree, and I want you to come and convince him.' He arrived, sat on the couch and told my father about the college. What do you study in Halacha, in Torah. My father sat with his mouth open in amazement. My mother asked: 'Rabbi Kupperman, if Rivka studies at college, will she be able to get married?' He answered her: 'Sure, half of our girls wear headscarves, come and see.' She was afraid that if I became educated, no one would marry me, that was the mentality.

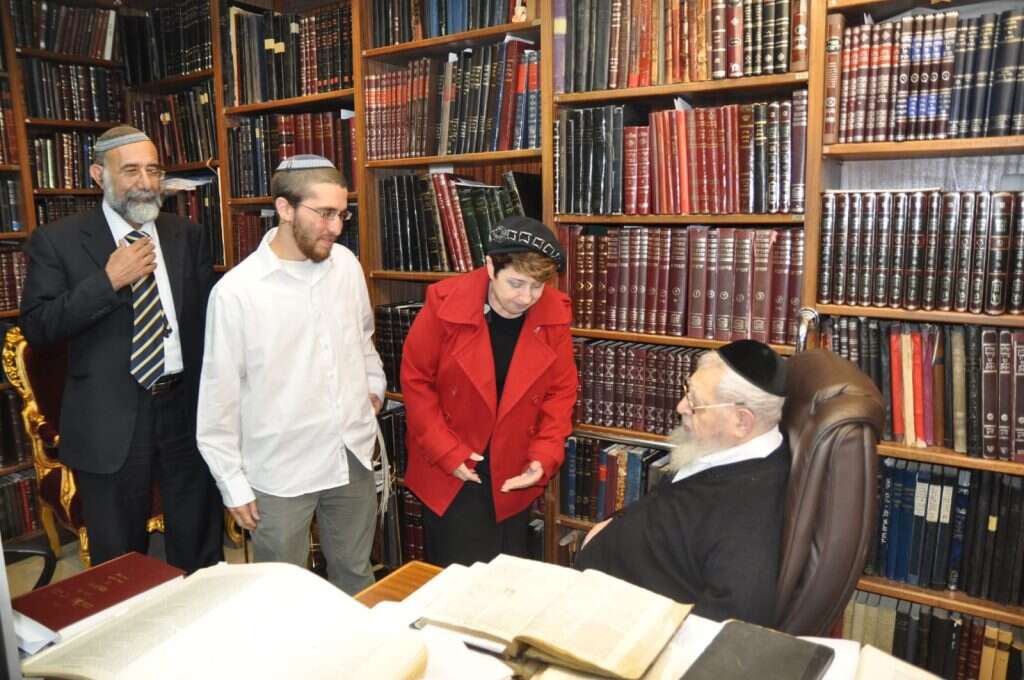

"For a long time, none of the girls at the college knew that I was Rabbi Ovadia's daughter. And listen, those were my best years. When we started studying the Bible, it was really hard for me to understand what they were talking about. At Beit Yaakov we had Rashi, maybe one more commentary, and suddenly they bring all the commentary and you have to go and compare. I came home and said, 'Dad, I don't understand what they're talking about in class. You have to help me.' He told me, 'No problem, I'll come back from class at ten at night, we'll have a get-together and study.' While he ate, we sat and studied, and that's how it went for a few months until I managed to get into things. Every evening he would end the class and say, 'How smart you are, how fast you learn, it's a pleasure to study with you.' Do you know what that does to a girl's confidence?

"Before the wedding, I asked my father: 'Yaakov has a knitted kippah, do you want him to change it?' He answered me: 'What does it matter what he has on his head? I care what's inside his head, and thank God his head is full.' There was a time when people around me influenced him and he changed to a black kippah. We came to visit my father, and he said to him: 'Where is your beautiful kippah? Go back to your quarry."

"Later, we took a course on how rabbis arrive at a halachic ruling, and the rabbi who taught us filmed a halachic ruling by my father about David Shemesh on Shabbat. At that point, they already found out that I was the rabbi's daughter. I came to him and said, 'Dad, they think that because I'm the rabbi's daughter I should know everything. So teach me, so that I can know.' Do you know how many hours he sat with me? It's a whole booklet. He told me, 'Climb the ladder, bring this book, that book, look at what it says.' We literally sat down and studied every book. My brothers would say, 'We didn't get to be a friend of Dad's like you are.'"

"Rebecca needs a bouncer"

Rivka (66) is married to Rabbi Yaakov Chikutai (68), the chief rabbi of the city of Modi'in-Maccabim-Reut. Rabbi Chikutai, who wears a knitted kippah, was a rabbi in the police and served in the Armored Corps. Rivka served over the years as an educational consultant and art teacher, and later was a Shas representative in the Histadrut and helped improve the working conditions of ultra-Orthodox and religious women. Today, she is engaged in the art of painting and mosaics and in training brides.

I ask to hear about the couple's acquaintance and matchmaking process, and Rivka agrees. She remembers how she first met, on her father's recommendation, with a guy who was described as "high-class," but the meeting was unsuccessful and lasted only fifteen minutes. "I arrived at the meeting, barely sat down, and the guy said to me, 'How come you're in college?' I replied, 'Wait a minute, I want to understand, what is your opinion about the college?' He said, 'I don't have my own opinion, I have the opinion of the great men of Israel.' I told him, 'Then why did you meet with me?' He said, 'I thought you were different.' I told him, 'I'm not different, the college and I are one. It was nice to meet you, hello and goodbye.' I told my father and asked, should I have continued to meet with him? He understood.

"Then another guy and another guy," Rivka continues, "and I tell my father what the guys are saying, and he says to me sadly, 'Why don't they teach them to speak in yeshiva? Why do they talk such nonsense?' He saw that nothing was going well, so he called my brother David and told him, 'Go to the Western Wall Yeshiva, the head of the Western Wall Yeshiva, Rabbi H. Y. Hadari knows Rivka, he teaches her at college. Ask him to find Rivka a matchmaker. Rivka is not suitable for a Haredi guy. So my brother David went and talked to Rabbi Hadari. Two days later, my father went to a certain wedding, and Rabbi Hadari was there as a witness at the wedding. My father grabs him by the hand and tells him, 'You're not going, I need to talk to you.' The wedding is over, my father takes him by the hand, puts him in his car and says to him, 'I sent you my son, so did you find him?' Rabbi Hadari replies, 'Yes, there is someone. His name is Yaakov Chikutai, I need to talk to him.'

"Rabbi Hadari goes to Yaakov Chikutai, tells him, 'Listen, there's someone, the daughter of Rabbi Ovadia.' Yaakov answers him, 'What's wrong, me? The daughter of Rabbi Ovadia? I'm not ready.' Rabbi Hadari tells him that he already told Rabbi Ovadia, but Yaakov didn't agree. Rabbi Avigdor Nebenzl (who also taught at the Western Wall Yeshiva; D"b) goes to Yaakov, tells him, 'Listen, Rabbi Hadari has already promised, go meet for ten minutes and say you don't want to. But at least meet, so that Rabbi Hadari won't humiliate himself in front of Rabbi Ovadia.' Then he agreed to meet with me for ten minutes, and he's stayed to this day," Rivka concludes with a smile, explaining the reason for his initial reluctance: "At first he was afraid - of the status, of everything. He thought I was a douchebag. We all know who the douchebag is between us..."

"We met on Hanukkah, and for four months we hung out in the bitter cold of Jerusalem," Rivka continues, recounting the period of their acquaintance. "He wouldn't agree to come to my parents' house until I promised that I was serious. Then I got sick with the flu, and he called our house to ask how I was. My mother answered the phone and said to him: 'Aren't you ashamed? She's sick and you're not coming to visit her? Come this evening.' He went, bought flowers, my parents received him. My father sat and talked to him about the community in Persia, Yaakov's parents were born in Tehran. They sat and talked openly. Yaakov had rabbinical certificates that he had received from my father even before that, so he knew my father as a rabbi who was examining, and thought that he was going to examine him. But my father just hugged and was happy."

Was it love at first sight ?

"The truth is, no, I thought he would help me do my college work," Rivka replies with a smile. "But then we talked and talked, and it's impossible not to love Yaakov. I don't know anyone who knows him and doesn't love him. Thank God, I won him."

"Before the wedding, I came to my father and asked: 'Yaakov has a knitted kippah, do you want him to change his kippah?' My father answered me: 'What does it matter what he has on his head? I care about what's inside his head. And thank God his head is full, he doesn't need to change his kippah.' There was also a time when people around me influenced him and he changed to a black kippah. We came to visit my father, and he looked at him and said to him: 'What? Where's your beautiful kippah?' And Yaakov apologized and said: 'No, Rabbi, they told me...' He answered him: 'Nothing, go back to your kippah, go back to your quarry.'"

Cry with the Agunot

The Chikotai couple live in the Massua neighborhood in Modi'in, a mixed neighborhood of secular and religious people. "I grew up all my life in secular, mixed neighborhoods, and I wanted to pass that on to my children," says Rivka, noting that her father lived that way for most of his years, until moving to their last home, in the Har Nof neighborhood. She says that Rabbi Ovadia never prevented his children from playing with their non-religious neighbors, and they were never ordered to lock themselves in the house. Not only did they, of course, never shout at cars driving on Shabbat, but her father also opposed the demonstrations that had previously taken place in the Geula neighborhood, in the square that later became known as "Sabbath Square," and forbade his children from taking part in events of this kind. Rabbi Ovadia, his daughter says, did not shut himself away in the beit midrash. He was "connected to the people, heard and made the voice of the public heard, connected heaven and earth."

What led her to write the book, says Rivka, was the awareness of the gap between Rabbi Ovadia's public image and the private person she knew. "No one disputes that he is great in Torah, but his leadership methods? No one knows. It burned for me, I felt it was my mission to make sure people knew, to provide balance. My father was a giant in Torah, but he was also a human being. If a woman came to him and cried to him, he would sit and cry with her."

Among the various episodes described in the book is the issue of the agunot during the Yom Kippur War and the effort made by Rabbi Ovadia to quickly get them released. At that time, an endless procession of wives of the missing, comrades in arms, senior and junior officers arrived at the Yosef family home, Chikotai recalls. Rebbetzin Margalit welcomed them all. As each of the war widows arrived, the Rebbetzin gave her a warm hug and sat her down on her lap. Tears flooded the room again and again as the women told their stories, and recalled various sayings and signs that might have helped with the permit process. The military personnel who arrived provided their own information and documents, and every detail that might have been useful was written down and added to the files.

Late in the evening, when the various visitors had left the house, Rabbi Ovadia and his wife would sit and process the day's events together. "Each one presented the side he had heard, the arrows that pierced his heart," describes Rivka. The rabbi then permitted 950 agunot, in a short period of time, "and he was not wrong in any ruling. There was one woman who he could not find a way to permit. He tried in all sorts of ways and could not. Finally, after a while, her husband suddenly appeared with crutches."

Rabbi Ovadia's involvement in the issue of the Agunot and his awareness of the terrible price that the war exacted also led to his well-known ruling on the issue of territories for peace. In parallel with the talks that took place later that decade between Israel and Egypt, the rabbi summoned the senior officials of the defense establishment. He consulted, researched, and questioned everyone. In a famous speech at a conference of the Rabbi Kook Institute in 1979, he stated that "if the heads and commanders of the army, together with members of the government, determine that there is a pikuach nefesh in the matter... it is permissible to return territories from the Land of Israel in order to achieve this goal, that you have nothing that stands in the way of pikuach nefesh."

The period in which he was intimately acquainted with the horrors of war was among the factors that led Rabbi Ovadia to his ruling. "I sat for months from morning to night, in battles, saints fell, of whom there was no trace left except bones and ashes," the rabbi said, as quoted in the book. "We collected testimonies from soldiers, and tears flowed from our eyes like water. We dreamed horrific dreams for six months. We immersed our heads in nearly a thousand cases of agunot, whose owners died cruel deaths. Can we afford for the blood of Israel to be shed like water? One soul is worth all the territories. We all value the commandment of settling the Land of Israel, but it would be unthinkable to abandon souls in Israel for any piece of land."

However, in an interview in 2003, Rabbi Ovadia sounded a little different: "When it came to autonomy in Gaza, I supported it, but signing agreements that would bring them into our homes? Inside our city? In the center of the Old City? It has nothing to do with this ruling, when handing over these parts also leads to a situation of danger to lives. Concessions can be made in remote places." Rabbi Ovadia later issued a clarification that in his first ruling he had only meant a situation of true peace, "However, our eyes see and understand that on the contrary, handing over territories from our holy land leads to a danger to lives."

"Quiet, Dad is studying"

Alongside the father's love that she received, Rivka also describes a childhood in which she was alert and vigilant, not to disturb him from his studies. "We were 11 children in a four-room house, where did we sit to play? Under the dining room table. We fought quietly, we cried in whispers. There was a holy word in the house: quiet, dad is studying. He must not be disturbed. Our children from the age of zero also knew, 'quiet, grandpa is studying, don't make noise.' On the other hand, he constantly helped mom. Not by washing dishes or cleaning the house. He had a 'children's corner' on the radio, we would sit and listen and he would feed us with a spoon. He would press our bellies and laugh with us and say, 'Here, there's a place here.'"

Before the days of glory came, the Yosef family also knew years of poverty and deprivation, but the rabbi continued his studies, which were most important. "My mother loved my father with an infinite love, and he returned her with great love. What admiration she had for him, for his life's work. When they first got married, she saved money for a long time to buy a cabinet for the house, and then my father wanted to print his book and he was short of money. Without thinking twice, she went up to him and said, 'Take it, it's for the book.'

"When we were kids, the biggest threat was 'I'll tell Dad.' It's not that he would punish us terribly, but the disappointed look was enough that we didn't want to face him. It was important to us to excel, for him to be proud of us. All my sisters know how to cook, because that's how we got compliments from him. My mom would serve the food, and he would say, 'Without Rivka, we wouldn't have Shabbat.' Like, what did I make, bureks? We grew up with this kind of support. I also taught my sons to cook, because as a child I was always resentful that only girls cooked."

As someone who grew up in the shadow of such appreciation for Torah study, how do you feel when you hear statements today that Torah students are idle and disconnected ?

"I truly believe, as my father believed, that studying Torah is the most important thing. Unfortunately, not everyone thinks like me, but not everyone is really capable of sitting down to study Torah either. You see a lot of guys hanging around, and they give all the Haredim a bad name. If everyone was in yeshiva, no one would open their mouths, there would be less shouting. The main reason they don't let guys enlist is because they're afraid they'll get spoiled. On the other hand, when my father saw someone not studying, he told them, 'Go join the army.' He didn't agree to anyone working for Shas if they hadn't served in the army. If you're going to work, serve in the army first."

When his eldest son Lior reached military age, he went to consult with his grandfather: "My father asked him, 'What does your heart want? What do you think is most right?' Lior told him: 'I want to go to the Seder yeshiva, and then enlist.' Dad told him, 'Go.' My son Adi was in the Memaram unit, an outstanding soldier, and he was proud of him. How he hugged him, what love he gave him. He never said, 'Don't go to the army.' He did say that the Torah is the most important, and I also believe that the Torah protects the people of Israel. During the Six-Day War, my brother came from the yeshiva and went up to the roof to see the bombings. Dad told him, 'No, no, your brothers are fighting in the army, you sit and don't take your eyes off the book.' During Operation Defensive Shield, my Lior was drafted. I called my father and cried, I begged him to pray for him. The next day he announced in class that it didn't matter that it was Chol HaMoed, everyone was returning to the yeshiva. "Because if there is a war, you return to the yeshiva and fight in the yeshiva."

The girls are involved in the ruling.

I ask Rivka how she would feel if one of her children wanted to take the opposite path and become Haredi. She smiles and tells of her daughter Marganit's youthful rebellion when she turned sixteen: "There was a time when she bought black shirts in large sizes and wore only black, not colorful. It drove me crazy. I came to my father and said to him: 'Dad, I have an only daughter, have you seen how she is dressed? She has started to go in a too-ultra-Orthodox direction.' He said: 'Okay, bring her, I will talk to her.' I brought her to my father. I came in, and he told me: 'I didn't call you Marganit, just Marganit.' He sat with her for half an hour, opened books for her, showed her halacha, said to her: 'Do you know how many halacha rulings I have written about beautiful clothing, about makeup, about nails? So many rulings, do you want me to erase my books? It is a mitzvah for a woman to look beautiful, you can dress modestly and beautifully.' After half an hour he opened the door and said to me: 'Now come in, I have talked to her. She agrees that now you should go and buy her colorful clothes. "And beautiful." I told him, 'Dad, tell her she doesn't have to wear it all the way to the floor.' So he told me, 'You should compromise a little too.' He knew how to give her that opening, to also maintain balance in her own way."

Rabbi Ovadia's daughters, says Rivka, had a hand in his rulings that touched on women's issues. "One day he called me, 'Rivka, bring all your makeup. I want to write a halachic ruling and I want you to explain to me what makeup is, how the red, the blue, the powders work.' He sat down and then wrote a halachic ruling that it is permissible to wear makeup with powder on Shabbat."

The conversation enters halachic territory, and Rivka calls her husband, Rabbi Chikutai, to join in. He provides another example of Rabbi Ovadia's female ruling, which his daughters had an influence on: the question of the husband's presence in the delivery room. According to Rabbi Chikutai, "The Ashkenazi rabbis said it would not happen and it would not happen. The rabbi ruled that it would, because it strengthens the woman. If during childbirth her husband is by her side, not even touching her, it helps her. There are other rabbis who have many daughters, but here they had an influence. They brought the external world into the world of the Torah for him."

"He heard from us how important it was," adds Rivka. "I told him, 'Dad, I won't be able to give birth without Yaakov.'"

"In general, the rabbi always liked to listen and then decide," continues Rabbi Chikutai. "Even when talking about returning territories, he gathered several leaders to his house, not together, and he would listen and study the matter. The rabbi was open to ideas. If they brought Torah, to the acquittal of the rabbis, to the strengthening of the fear of God, to the prevention of dropping out – he went for it. Satellite Torah lessons were an innovative idea. He went with it, he loved innovation. They brought him a microwave and he sat down, examined it, and explained to him how it worked. Platter on Shabbat – all the Ashkenazi rabbis disapproved. They said, 'What's the matter, it's like cooking.' The manufacturer came to Rabbi Ovadia. The rabbi told him, 'Leave it here, plug it in and go.' He left it for 24 hours, and the rabbi observed, studied, put eggs in it and checked what was cooking, how it came out. He did all the tests, and then gave approval that a platter was permitted on Shabbat. It was a revolutionary ruling. He didn't say, 'New is forbidden by the Torah.'

"There are rabbis who don't always open their eyes to the public, to look at what's happening on the ground. There are Torah instructions, but there's reality outside, and you have to know how to integrate that. There are many good things in Haredi society. The ban on using the Internet is important. It's not good for children, and we as adults sit with it all day. On the other hand, if it's a tool, you have to know how to use it. The ban should be proportionate."

Aliyah to the Torah for those who violate the Sabbath

To demonstrate his father-in-law's path, Rabbi Chikutai goes to the study, returns from there with Responsa Yachava Da'at, Part Seven, and opens it with a question mark, which deals with "admitting children to a Torah school when their parents do not observe Torah and mitzvot." Rabbi Ovadia is asked there about parents who desecrate Shabbat and have a television set in their home, and want to enroll their children in a Torah school. The administration wants to demand a commitment from them to observe Shabbat, otherwise they will not accept their children into the school. Is this the right thing to do?

"Certainly, one should not feel," Rabbi Chikutai quotes Rabbi Ovadia, "that parents who come to enroll their sons in a Torah school, who desecrate Shabbat with disgust... otherwise they would not have come to enroll their sons in such a school, when they have other schools in the neighborhood... The very fact that they come to enroll their sons in such a school testifies to the purity of their hearts, and therefore their children should be brought closer and not pushed away, even without conditions, because as we know, coercion pushes them away. And isn't there great hope that time will take its course and the sons who study in a Torah school will return their parents to repentance... and if we come to force this on them, one should feel that it will cause them a burning insult and a compulsion of conscience and an injury to their honor and they will leave a source of life... Therefore, one should act wisely and wisely, bringing closer and not pushing away. And also in the matter of television, there is no need to rush the time to remove it immediately from the house, especially if they claim that it is used only during the news."

Rabbi Ovadia's first rabbinical position was as deputy chief rabbi of the Jews of Egypt, during the establishment of the state. Rabbi Chikutai: "He arrived there, and suddenly he discovered a new reality. People who come on Shabbat night, pray, make kiddush, sing Shabbat songs, in the morning they pray again from six to eight and have Shabbat dinner – and then at nine they go to work. They write, answer the phone, everything. At four in the afternoon they return home, time out, Shabbat again. What do you do with people like that? Yell at them, 'You are criminals'? They told them they could not go to the Torah, and Rabbi Ovadia wrote halachic rulings that it is permissible and that they should be brought closer."

Rivka adds and tells about her brother who visited them in Modi'in, and stayed at the synagogue located in the heart of a secular neighborhood. "Afterwards he came and told my father, 'You know, people come there by car on Shabbat.' But my father was fascinated by the embracing treatment they receive in the synagogue."

The Chikutai couple feel like a bridge between the ultra-Orthodox and religious Zionist worlds. "In Shas, we are considered religious Zionism. And in religious Zionism, we are considered Shas," says Rivka. This unique position was expressed after a sharp speech given by Rabbi Shalom Cohen, Rosh Yeshiva of Porat Yosef and a member of Shas' Council of Torah scholars, in July 2013, during the "Brotherhood" government of Bennett and Lapid. Rabbi Cohen uttered harsh words against religious Zionism, and among other things said: "As long as there is a knitted kippah, the chair is not complete. This is Amalek... are these Jews?" Tempers flared not only on the street, but also in the Chikutai family home. "I knew he wasn't talking about me but about politicians, but my children took it very hard. They told me, 'Mom, you can't keep quiet,'" recalls Rivka.

Given the rabbi's medical condition at the time, just months before his death, it was difficult to get through to him. Rivka had to write down the words and send them with her husband. Rabbi Ovadia responded with surprise: "Is that what Rabbi Cohen said?" On Shabbat night, when the time for the regular lesson arrived, despite his physical condition and the pain he was suffering, he insisted on coming down and delivering the lesson. At first, he explained that Rabbi Cohen was referring to political figures, but then he expanded on his worldview. "Does the kippah indicate who the person is? They are all loved. I have many students with knitted kippahs. And I never distinguished between my students. When I was able, I would go to Seder yeshivahs and give Torah lessons there, and they would be happy, and I would also be happy with their happiness."

"If I hadn't been there," says Rivka, "no one would have drawn his attention to it. In retrospect, we know that was the last lesson he went downstairs. He had excruciating pain, he couldn't stand on his feet, but he insisted on going down and talking about it. How can I not love my students? So many of his students had knitted kippahs. My father came from the field, you saw his feet everywhere."

Harassment? Go straight to the police.

Against the backdrop of the MeToo era and the rise in awareness of sexual crimes, Rivka testifies to her father's attitude towards these cases: "If mothers came and told about sexual harassment, he would say to quickly contact the police. When we lived in Tel Aviv, someone came and told about a rabbi my father knew, who harassed her daughter. My father told her: From here you go straight to the police. The rabbi also spoke out against violence by men against women. A woman who wants a divorce because he beats her, to this day there are judges who say shalom beit. He would immediately say a get. He was the first to put men in prison who did not want to give a get to women who were victims of violence. He was not willing to forgive, to listen at all. He called it the redemption of captives, that was his mentality. He would say, 'Everyone who comes to the court is like my daughter.'"

Rivka shows me a picture of a memorial service for her mother, attended by her father. The family is seen there together around the grave, without separation between men and women. "This picture is important to me, because you see how every year he went to the cemetery with us. They wanted to separate my father's grave, so that the men would stand by the grave, and the women across the fence. And I said, 'Excuse me, my father accepted women in his life. Why can't women go to his grave?' We insisted that the whole family come together and light the candle. It's important to us to hear the Kaddish, to be there together." In the book, she also describes various incidents in which they tried to introduce separation at family events, and she and her sisters fought against it and gained the support of their father.

"He gave us everything," Rivka ends our conversation, and the longing is evident in her voice. "At seven o'clock, all the brothers sat and talked, and suddenly we saw that each of us was sure that my father loved him the most of all, and each of us felt that father was pleased with the path he had chosen."

Not yet subscribed to Makor Rishon? Join and receive a free month as a gift

*The promotion is for new members in accordance with the promotion regulations.

Related articles

The connection between the laws of impurity and purity and the tragic deaths of the sons of Aaron

The laws of impurity and purity in the book of Leviticus are surrounded by a narrative framework that gives them conceptual meaning and clarifies the importance of boundaries.

From the attic to the family room: outlines of the image of the Israeli home

The 77th Independence Day is an excellent time to take a look inside – not only into Israeli history and identity, but also into the most...

Patriotic Fashion: Israeli Initiatives That Instill Hope in Us

Embroidered shirts, commemorative jewelry, and T-shirts about the surrounding communities whose proceeds are donated to resilience centers – Israeli brands and designers prove that fashion can also...

Categories

Receive the newspaper for one month as a gift

*The promotion is for new members in accordance with the promotion regulations.

All rights reserved to "Makor Rishon" 2021 ©

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment